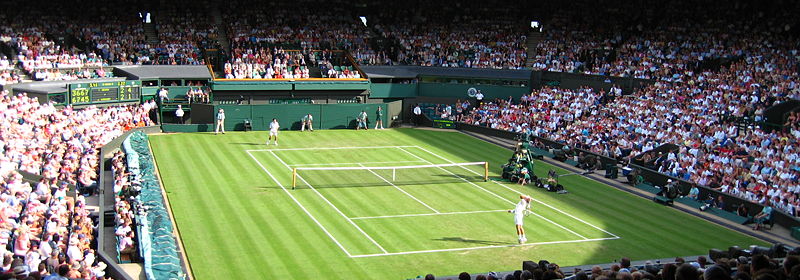

It’s time to dust off your racket and wrestle the tennis balls from your dog’s mouth. Wimbledon 2015 is upon us! Wimbledon is as much a feature of the British summer as barbecues, Henley Royal Regatta, and summer rain. Whether you grew up shouting ‘Come on Tim!’ or ‘Don’t cry Andy!’, Wimbledon seemingly captivates every generation of the British public for two weeks. But as spectators at SW19 reach for their scones, jams, and Pimms, I wonder if our perception of tennis is similar to Shakespeare’s? Was it all strawberries and cream and Henman Hill in the sixteenth century too? Using Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) as my experienced, disciplined, but approachable coach, I cast a hawk-eye over Shakespeare texts to look for references to tennis. So if you’d like to take your seats at centre-court, I will serve up some aces for your enjoyment.

Quiet please, Will Shakespeare to serve. First set. Play!

Perhaps the most direct reference to tennis in Shakespeare’s texts comes from Act I Scene ii of Henry V. This scene depicts King Henry V in his royal throne room discussing with his advisors the validity of his claim to the French throne before he meets with Ambassadors from France. When the Ambassadors arrive, they provide tennis balls that form a ‘tun of treasure’ (line 255) they give as a gift to ensure ‘the dukedoms that you claim / Hear no more of you’ (256-257). The tennis balls are used in place of ‘treasure’ in reference to Henry V’s wild past, and imply that the Dauphin of France will not treat Henry V with respect as he attempts to dissuade the King from invading France. King Henry V’s response to the Ambassadors uses a tennis metaphor and tennis puns as a thinly veiled threat to suggest that the war will be like a game – and that the victor will claim the kingship of France: ‘When we have matched our rackets to these balls, / We will in France, by God’s grace, play a set / Shall strike his father’s crown into the hazard’ (261-263). Later in the speech (and with considerably less subtlety) Henry V informs the French Ambassadors that ‘This mock of his / Hath turned his balls to gunstones’ (281-282).

Tennis puns punctuate Henry V’s threat on France in this famous speech; for example, the use of the word ‘crown‘ (263) in this context could refer to the Royal crown or to the method of scoring which was derived from betting on the game. According to several editions of the text, each scoring point was called a denier d’or (15 sous) until the first player to reach 60 sous won the final point, which was called ‘couronne’ or ‘crown’. Therefore, the scoring system we use today in major lawn tennis tournaments like Wimbledon is strikingly similar to the scoring system used in real tennis when Shakespeare wrote Henry V. It may be a stretch to say that if Andy Murray wins the final point in the final game in the final match at Wimbledon he would win a ‘crown’ — but he would certainly become British sporting royalty!

But Wimbledon isn’t just about tennis, oh no! It’s an opportunity for thousands of spectators to embrace the British summer – and what says British summer louder than strawberries and cream?! A quick search through Shakespeare’s works came up with nine references in total for the search term ‘strawberries’. From Othello to The Tragedy of King Richard III to Henry V, strawberries can be found in the Bard of Avon’s texts as easily as they can be found in the stands at centre-court. According to the notes in the Michael Neill edition of Othello, the strawberries embroidered on Desdemona’s handkerchief in Act III Scene iii are ‘capable of a remarkably contradictory set of meanings’. On the one hand, the strawberry’s simultaneous flowering and fruiting made it an emblem for the chastity and fertility of the Virgin Mary in Christian tradition. On the other hand, the strawberry was often used in Renaissance Emblem Books with a serpent coiled around its leaves to signify deceit. It is Othello’s recollection of this paradoxical handkerchief that seemingly sets off his fit in Act IV scene i, and that turns his own heart to stone as he envisages it once again, clasped in Cassio’s hand, just before the murder in Act V scene ii. So remember the charged symbolism of the strawberry when you prepare a bowl to eat with the Wimbledon Final!

Game, set, and match – Shakespeare wins six love, six love, six love. (Despite ‘love’ being an ever-present motif in Shakespeare’s sonnets and plays, he would not have punned on the tennis term ‘love’ as, according to the OED, it was first recognised in scoring games in 1742.) So that’s it I’m afraid. The clouds are forming overhead and the covers are being rushed on to preserve the pristine playing surfaces at Oxford University Press, so farewell, and we’ll see you next year for Wimbledon 2016!

Daniel Parker is Publicity Assistant and handles publicity for online products such as Oxford Scholarly Editions Online. The electronic environment of Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) provides a new research method and tool for the reader, who can quickly examine the history of the scholarly editing of a work or see instantly how a particular word used in a text has changed over time. OSEO makes it possible for students and scholars to interrogate texts in ways that could never have been done before.

Image credits: (1) Centre Court Wimbledon. Picture taken in 2005 by Spiralz. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Screenshot of OSEO taken by Daniel Parker.

This article first appeared on OUPblog here.

Follow Daniel Parker on Twitter @dgp202

Follow OUP on Twitter @OUPAcademic

Recent Comments